Spaces can create a sense of social inclusion or isolation.

—Hughes et al., 2019, xi

Space & Inclusivity

Regardless of how we individually perceive them, environments inherently offer opportunities for shared experience (Pourbagher et al., 2021). As current best practice in education moves toward fostering authentic inclusivity, there is a salient need to better understand how physical design and built environments can impact collective learning (Barrett et al., 2017; Cleveland & Fisher, 2014; van Merriënboer et al., 2017). Feelings of connectedness and inclusivity are naturally fostered through shared experiences in safe, universally accessible spaces, so the facilitation of inclusivity in educational settings may well be improved with greater understanding of spatial factors that both amplify experiences of belonging and promote lasting learning.

On this page, through the lens of student need, you’ll explore different factors to be considered when creating inclusive environments. I’ve included introductions to universal design (UD) and universal design for learning (UDL) as these concepts are pathways to inclusion. You’ll also see video resources highlighting current research and practice from around the world that relates space and place to inclusion.

Understanding the difference between location and place is key in cultivating effective and successful inclusive practice in our classrooms. It is particularly tied to the concept of belonging, which Berryman and Eley (2019) also identify as key to student success and wellbeing. Moore (2021) claims, “It’s not just about who we are, but who we are in a place, and who we’re with in a place over time.” With connections to indigenous world views, the essence of place has as much to do with community and shared history as it has to do with the land or built space. Giving learners access to places where they can use space flexibly, forge connections, and practice ownership over their decisions will ultimately support individualization, an underpinning principle of place-based learning (Barrett et al., 2017).

Moore says place-based perspectives help us understand that inclusivity is about community (not location); identity (not compliance); and belonging (not existing). “Every community is diverse, and every diverse identity needs to belong in ways that are meaningful to them” (Moore, 2021).

Everyone has a disability, says Michael Nesmith (2016) in his TEDx Talk. It might be temporary, like being pregnant or old or young, but given the right circumstances, at some point our disability will mean we face barriers where others do not. Nesmith frames disability as contextual and situational, supporting the theory that ability (or lack thereof) is not absolute, but environmentally-dependent. We need only imagine a common physical or social circumstance that might impact a person’s opportunity to participate in everyday life—say, a visual sign in front of someone who is blind, or a coat hook that is too high for a child—and we can see how the environment could be seen as ‘disabled’ rather than the individual (Field & Jette, 2007). Universal design helps cultivate belonging through accessibility, and in doing so, makes a tremendous difference for students (Watkins, 2005).

Some important takeaways:

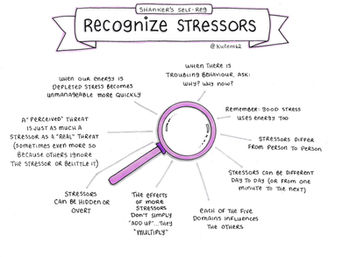

- Stress compounds in the body and takes energy to manage.

- When our energy is low, stress is more challenging to manage.

- Perceived threats can cause the same stress response as real threats, so we need to respect our students’ perspectives. Explaining why something shouldn’t feel stressful doesn’t make it any less of a stressor.

Some environmental strategies to consider in the classroom:

- Quality air circulation with open doors and windows, standing fans, etc.

- User-controlled blinds can help block direct sunlight and distractions outside

- Flexible seating options let students work comfortably

- Access to multiple modes of representation, engagement, and expression (e.g., provide verbal and written instructions; offer access to spatial and material resources for writing, drawing, enacting, speaking, etc.)

- Options for group, low-density, and private learning spaces

- Soft furnishings and fabric wall coverings for sound-absorption

Try printing this checklist, developed by The MEHRIT Centre. Keep it handy for a quick "sense survey" throughout the school day. Your students will thank you!

There are a variety of ways we can facilitate self-regulation in our students. Kristin Wiens (2017) illustrates some of these in “Features of Self-Regulating Learning Opportunities.” To offer students ways to manage their responses to stress, we can:

- Broaden learning content to incorporate different topic areas for a given subject

- Allow students to demonstrate their learning in creative ways

- Include a mix of independent and social forms of learning

- Include students in making choices; give them ownership over their learning

Source: Butler et al. (2017)

Differentiating instruction is a way of thinking; a process of making decisions in the moment. As educator Rick Wormeli (www.rickwormeli.com) says, fair doesn’t always mean equal, and this concept applies to differentiation as much as to universal design. When it comes to differentiating our instruction, there are three main areas to consider: content, process, and product (Tomlinson, 2014).

Give students choice around how they meet your learning objectives with variable content. Allowing them to choose an area of interest for their writing and research will often inspire greater learning than if you insist they focus on a specific assigned topic to practice their writing skills. Changing how you group students can differentiate the process of learning—alternate between mixed ability groups, same ability groups, pairs, and student choice, for example. We need to keep our eye on the prize: what are the learning objectives and what are the best roads for students to get there? Often, if given the chance, students will tell you what learning approach works best for them, making your job as teacher simply to support them in taking that approach. By incorporating flexibility and choice into our teaching, we can encourage ownership over student learning, which is known to be a key part of individualization and facilitating success in learning spaces (Barrett et al., 2017).

To meet the needs of a diverse group of students, we can:

- Explore bias and assumption. People think differently and see the world from different perspectives. Age and ability are not the only elements we need to consider as teachers.

- Build relationships with students. Understanding how our students experience learning can help us increase their sense of belonging. Aim to use all students’ names with the same frequency (instead of just keen learners and those with challenging behaviour).

- Examine your content and curriculum. Look for opportunities to include authors, speakers, mentors, case studies, examples, and learning styles that reflect the diversity of your students. When students see their own experiences and cultures in course material, they will better connect and increase their academic performance.

Source: WTCSystem, 2020

“Don’t limit me.”

On behalf of herself and all students, with and without disabilities, Megan urges teachers not to limit people with exceptionalities by thinking they can’t learn in a general education classroom; by thinking they will always need someone to help them; or by lowering your expectations for them.